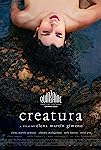

Eye For Film >> Movies >> Creatura (2023) Film Review

Creatura

Reviewed by: Nikola Jovic

Being brave and daring — both things this movie has been praised as — is usually associated with seizing something long kept out of reach, or disregarding moral customs. However, Elena Martín Gimeno's sophomore tour de force of the pure id, shows us that owning up to our sensitivities and being affectionate can be the bravest and the most uncomfortable thing you can do. Creatura (2023) premiered at the Cannes 2023 Directors’ Fortnight selection, walking away with the Europa Cinemas Label prize for best European film.

The film begins with Mila (played by the director herself) and Marcel (Oriol Pla), a couple in their thirties, moving into Mila's family home in the coastal area of Catalonia, which had been abandoned for some time. Although things seem to be going well for them, an underlying sense of uneasiness is palpable. Mila experiences unsatisfied sexual urges, while Marcel remains uncomfortably distant, avoiding eye contact with Mila during intimate moments, as though he would rather be someplace else. Due to the stress of returning home and having a troubled relationship, Mila’s curious condition of rashes all over her body starts to intensify. At least she believes that it’s stress-related. It’s at that moment that we’ll get a couple of sections from Mila’s past: her adolescence and early childhood, that dwell on subjects of sexual awakening and (in)appropriate behavior. These experiences of feeling inappropriate, ricochet through her unconscious mind as repressed beliefs that what she is feeling is shameful.

A couple of the most striking stabs at this emotional wound are instances where the words of Mila’s father echo through the words of her boyfriend. The father Gerard — played warmly yet firmly by Alex Brendemühl (as old) & Marc Cartanyà (as young) versions of the character respectfully — scared of perhaps crossing the line between playful and sexually suggestive by letting his five-year-old (and in later scenes teenage) daughter have her way, Gerard tells her that she makes him feel uncomfortable. Something that Marcel will repeat as well during their lovemaking. Making her feel like she’s not a human, but more of a creature. One soon realises that we’re not dealing with a typical coming-of-age story or story about trauma, but of nuanced realisation of Electra's complex and its possible roots.

Putting such genre labels onto the film gives us a false impression that we know the overall shape of the story, while nothing could be further from the truth. One of the driving propellants is a very subtle play on points of view. While flashbacks are motivated by the events in the present, they’re played out in such a manner that the viewer, as an impartial observer, notices and walks away with different takeaways than the protagonist herself. The feeling is as if we’re seeing the two miners digging under the same mountain, but from different sides, and we’re just waiting to see when they are going to meet in the middle and what’s going to happen then. The problems in Mila’s and Marcel’s relationship, mysterious rashes, and sexually suggestive dreams in the beginning set up certain suspicions, while the flashbacks themselves never answer anything directly, instead leaving subtle breadcrumb trails to give us just enough of a lead so as to believe that we know more than Mila, even though we’re witnessing her flashbacks. What makes this even more interesting is that it subverts the biggest cliche behind abuse or trauma.

We often attempt to pinpoint the sources of our self-destructive tendencies, but these attempts usually amount to mere guesses about their origins. Perhaps because if someone or something is responsible for our destructive tendencies, absolves us of having to stand up for our desire. Gimeno first sets up expectations of the traumatic sources for the problems in the present, but the set-up doesn’t amount to any explosive event, but instead to nothing much at all. It showcases us the workings of the unconscious and how seemingly uneventful occurrences have the capacity to echo in our psyche, take a new shape, and grow within us into life on their own. Growing from within until it completely subsumes us. Trauma here isn’t a switch turned on by a force strong enough to propel it into being, but instead, it’s a slow-burning reflective state. An itch in desperate need of scratching, yet it seems that almost nothing can.

Given that a lot of this film relies on veiled implications, much rests on the central performances, as we briefly alluded to earlier, but the greatest weight rests on Gimeno. She not only keeps up with the character but also connects the 25-year-old Mila with her five-year-old and 15-year-old selves (both played in a touching and heartfelt manner by Mila Borràs and Clàudia Dalmau). She rises to the task and adds layers of depth to the jaunty and saucy role of Mila, putting herself in extremely vulnerable situations as an actress. This ultimately becomes her biggest directorial stamp on the film. The direction mostly doesn't draw attention to itself, except in rare instances of dream sequences and intriguingly ominous sexually charged scenes, with the most striking images left for the very end, which imparts a sense of deliberate gesture. Once you see someone completely surrender themselves, it serves as a driving force for everyone else to give their all, feeling comfortable in following their director through the slippery, yet vulnerable terrain.

Reviewed on: 26 May 2023